Claim to fame | Chris Galvin interview — Square Ball 20/1/23

Lad of Leeds

Written by: Rob Conlon

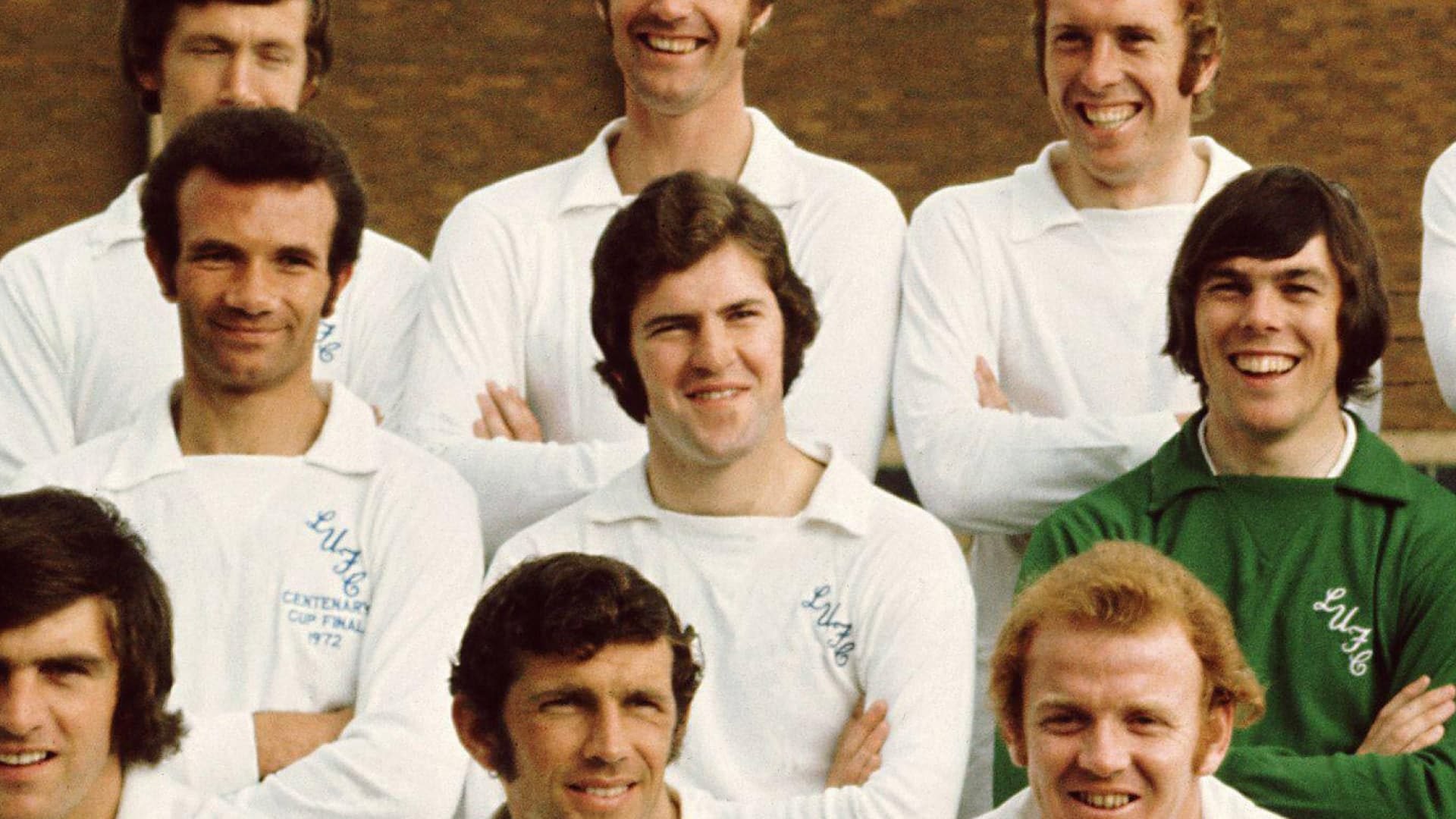

Competing with icons like Billy Bremner, Eddie Gray, and

Jack Charlton, there is no shame in not being the most recognisable face in

Leeds United’s 1972/73 squad photo. Standing between Paul Reaney and David

Harvey, Chris Galvin might not immediately come to mind when thinking about Don

Revie’s side, but he has a claim to fame that belongs in the legend of Super

Leeds.

“The stepover, I think that was my trick,” Galvin says. He’s

laughing, but he’s not necessarily joking. “I’m not bothered what anybody says.

I should have claimed it. I lacked pace, I wasn’t the quickest player, but I

was so keen on my game. I used to have a lovely body swerve, but full-backs got

quicker, so it stopped working. I learned this stepover, and that really put

players off balance. I don’t know why to this day. Lads would fall over; there

were times when I stood there laughing at them. It gave me an extra yard to

either get a cross or a pass or a shot in.

“That’s my one claim to fame, I say I invented that. I can

never prove it. I think Eddie Gray started using it later on as well. I’ll

stick to my guns and say I was the first player to use that. It worked that

well that all of a sudden you’d watch everybody doing it. Nobody can prove me

wrong!

“But it was done for a reason, and it worked. I used to do

it with my back to players as well. I’d do the same trick with a player up my

back and they’d disappear. It was weird. I used to piss players off, because

they couldn’t understand why the ball didn’t move. I spoke to a lot of lads I

played against and they’ll say, ‘Why on earth did I fall for that?’”

Born and raised in Huddersfield, Galvin joined Revie’s Leeds

as an apprentice and spent five years on the fringes of the first team. His

seventeen appearances were enough to make sure he was immortalised in Ronnie

Hilton’s song, The Lads of Leeds: ‘And goalkeepers shiver whenever they see —

Mick Jones, Allan Clarke, Peter Lorimer, Johnny Giles, Eddie Gray, Paul

Madeley, Rod Belfitt, Chris Galvin, and uncle Don Revie and all.’

Galvin’s younger brother, Tony, was also a professional

footballer, winning back to back FA Cups and a UEFA Cup with Tottenham. The

siblings are the subject of a book written by David Saffer to be published

later this year, titled Galvanised. Tony was signed by Spurs after being

spotted playing non-league football while studying Russian at Hull University.

For Chris, school was always second to sport. He was a “football fanatic” who

also played cricket for Yorkshire Schoolboys alongside former England wicketkeeper

David Bairstow, the father of current England batsman Jonny.

“Even after I signed for Leeds I still played cricket,”

Galvin says. “I played as much as I could during the summer. I must admit, I

wasn’t particularly allowed to. I got told not to play, but I sneaked some

games in. I couldn’t finish my cricket.

“I went to a grammar school, which I hated every minute of

because there was no football. We played rugby union. I finished up playing

rugby union for Yorkshire as well. I could play sport, couldn’t I, and that was

my interest, so I got to like rugby union, but there was no football at all. At

fifteen I got half a dozen O-levels and told the headmaster I was leaving. I

can remember him saying, ‘What an earth for? You can go on to sixth form and

hopefully university.’ I said, ‘I’ve got a chance to sign for Leeds United.’ It

still didn’t impress him at all. He said, ‘Well, I think you’re making a

massive mistake.’

“Because I didn’t play at school I played in the local Red

Triangle League. Under-16s was the youngest age group then. At ten, eleven, I

was playing Under-16s, which doesn’t happen anymore, does it? I was never a

hard, tough player in a lot of ways, but what I did find out was that you got

kicked and nine times out of ten it didn’t hurt, so you got up and kept going

against bigger, stronger lads. I think most lads at that age found that. It

wasn’t unusual. If you wanted to play football outside of school you had to

play above your age group, which I don’t think did us any harm.”

Leeds weren’t the only club interested in signing Galvin

when he left school, but sealed the deal when Revie’s chief scout and assistant

manager Maurice Lindley visited his family home. “Leeds United — it’s like

Manchester City coming for you now, you don’t really think twice,” he says.

Life as an apprentice at Leeds meant training under the fearsome coach Syd

Owen, before Galvin turned professional at seventeen.

“Syd was funny, he was dead straight,” he says. “We cleaned

the ground, we cleaned the boots, we swept up. You were mugged about a lot. Syd

Owen was there telling you, ‘This is doing you good. It’s making you better

men. Better individuals.’ It wasn’t easy being an apprentice then. You were

there all day. It was just like a job. You’d do all your chores in the morning

then train mainly in the afternoon.

“At seventeen you had the chance to sign professional and

then all those chores stopped. Life did change then. It was 100% football.

Still with Syd a lot, training separate from the first team. I think after a

year I got into the first team. Revie only had about sixteen or seventeen in

his squad who trained together all the time and travelled all the time. You

virtually went to every game as a squad member, which made it hard because the

second team also played on a Saturday.

“I spent a lot of time with Joe Jordan. He signed around the

same time, and we went into the first team squad around the same time. You

weren’t treated badly at all. You were part of it all. You trained every day,

travelled every Friday night, wherever you were playing. But there was still

that gap between Billy Bremner and me, if you know what I mean. It’s just human

nature. It was daunting to start with. I mean, we must have been the best side

in the world.

“All the training was small-sided games, which Revie swore

by. There’d be a squad of sixteen, so it used to be eight-a-side. I played for

a lot of clubs after Leeds but there was never that intensity in the training.

If Revie didn’t see it, he’d say, ‘Right, finished. In you go.’ You either

played it right or he wasn’t interested. You’d do a few sprints after and that

was it. But the small-sided games were so intense, and it showed on the field.

They were as fit as anybody, if not more so.”

Two days after his eighteenth birthday, in November 1969,

Galvin made his senior debut for Leeds in the European Cup, replacing Eddie

Gray for the last ten minutes at Ferencvaros. Leeds had won the first leg at

Elland Road 3-0 with a display described by Revie as their best performance in

his eight years as manager. No British side had ever won at the Nep Stadium in

Budapest; Galvin came on with Leeds 1-0 up, just in time to join the

celebrations as Mick Jones and Peter Lorimer made it a repeat of the first leg

scoreline.

“I did reasonably well when I came on,” he says. “It was

quite an event in my life to start off at that age. Ferencvaros were quite a

good side, they were a big name. All of a sudden Leeds United were competing

and beating the top sides who over the years had won European Cups and this,

that, and the other. That was the start of the next four or five years, when we

did become, for me, one of the best sides ever.”

That presented Galvin with a problem. With Eddie Gray and

Peter Lorimer ahead of him on either wing, getting into one of the best sides

ever wasn’t easy. Galvin’s first opportunities in the league came at the end of

the 1969/70 season, when Revie was forced into resting the bulk of his

preferred line-up as Leeds’ assault on the league title, FA Cup, and European

Cup led to a crippling fixture schedule.

Leeds won only one of their final six league fixtures,

beating Burnley 2-1 at Elland Road. Galvin started in the number 10 shirt,

getting the perfect view as Eddie Gray scored his two greatest goals, chipping

Burnley’s goalkeeper from thirty yards before leaving a trail of defenders in a

heap on the floor and firing into the bottom corner after a trademark dance of

dragbacks.

“I had a good game that day,” Galvin laughs, “but Eddie had

a better game! I was desperate for any match, so at the end of a hard season

when Revie was resting a few I’d get the odd game, but it wasn’t enough for a

young lad.

“I did get frustrated in the end. I admit I had a lack of

pace, but to keep yourself as quick as you possibly could you needed games. I

was fit physically, but I’d not enough game-time. It did tell, I lacked that

half a yard. The only way you get that is by playing regularly. I got really

wound up about it and thought, ‘I need to get away, I need to play games.’

“Revie always had this mentality that you were never an old

player until you got to 22, 23. The number of times I’d go into the office and

it was always the same message, ‘You’ve got to bide your time. Don’t get above

yourself. Just wait.’”

Galvin waited for Revie to start refreshing his team, but

lost patience when Leeds tried to sign Asa Hartford from West Brom, only for

the transfer to collapse when the midfielder’s medical revealed he had a hole

in his heart.

“I can remember this as clear as hell,” he says. “We always

had a full-sized game on a Thursday. I played in the first team with Asa

Hartford. I think Giles played in the opposition team. After the game I went in

and Revie told me, ‘I told you if you bide your time you’d be playing Saturday.

Asa’s playing instead.’ I thought, ‘Well that’s it.’ That was the first sign

that Revie was going to change the side. It was probably getting to the older

end then, and I think that was his plan to make a new team.

“Then on the Saturday morning I went into the team meeting

and Asa Hartford was sat crying in the corner. I said, ‘What’s up with you?’ He

said, ‘You’ll hear about it,’ and disappeared. It was when they found a hole in

his heart so they pulled out of the transfer. I was sub that day, and that

really made me angry, because I thought I was playing. I was meant to be

playing, but he reverted back to his old side.

“I think that was the day Revie thought that was it, he was

going to stick it out with his normal side, his successful side, and see it

through. I think his plans then of building a new side disappeared in my

opinion. And he went on to win other things with the same side so it’s fair

enough, it was a good decision. That was his one flaw in my opinion, that he

stuck to the same team of twelve, thirteen, fourteen players. But they were

successful, so what can you say?”

Galvin eventually left Leeds in 1973, joining Hull City. It

was for the benefit of his career, but that didn’t make it an easy decision.

“One season, and it’s unbelievable to think back, I played

something like four full ninety minute games in total across the first team and

reserves. That can’t be right, can it? You can’t be at your peak. I’m not

grumbling about it because it was the situation at the time, but it wore you

down. It was an exciting period, but I was a football fanatic. That didn’t

include standing around watching other lads playing.

“It was far from a relief to go, because I knew what I was

leaving. It was just something I had to do. Revie kept telling me, ‘Don’t go.

Sit and wait.’ Eventually I just said, ‘I can’t. I can’t wait any longer.’

Remember, it’s a short career. And it was nothing to do with money. It was just

purely wanting to play football at the highest level I could. I was confident

enough to think if I got away now there was still time to get back up, but it

doesn’t happen. I look back and think, you only move down when you have to. I

don’t regret it because I’ve had a good life in football to be fair. I’d say it

was a mistake, but at the time I thought it was something I had to do. It was a

must.”

Three years later, he was joined at Hull by his former Leeds

captain, Billy Bremner.

“That was probably one of the highlights of my personal

career, because he was always my hero. To me, Leeds United was Billy Bremner. I

don’t think they’d have been the side they were without him. You could have

replaced anybody else, but you couldn’t replace Bremner. He was the life and

soul. For me he was a genius. One of the best ever. Everything about him, not

just his energy, but his ability. People say he was a little terrier and he’d

run around and get stuck in, but that was a small part of his game. He was

technically brilliant, a fantastic player.”

Galvin ended his career by moving to Hong Kong, where he

worked as a player, manager, and agent. He worked alongside the PFA, finding

moves for other players coming towards the end of their careers who needed to

continue earning.

“The last thing a footballer wants to do is start working!

We were definitely spoiled with our career, so any chance of carrying it on

we’d snap your hand off. Some abused it, and really went there just to have a

good time. A lot knuckled down and did well. George Best came out and they

sacked him halfway through his second game. I’ll never forget that because I

was sat there watching. They took him off at half-time and said, ‘Go home,

we’ve booked your ticket.’”

Galvin eventually returned to Huddersfield, where he has

lived ever since. He says he is not one to attend reunions and social events

with his former teammates, but did accept one invitation, in 2019, when he

joined Revie’s squad in being awarded Freedom of the City at Leeds Civic Hall.

“I thought, ‘You can’t say no to that.’ Looking back it was

sad, because it wasn’t long after that Trevor Cherry died, Norman Hunter died,

Terry Cooper died. And they looked well. I think back to that night and Norman

Hunter looked as healthy as ever.

“That night made me realise what a fantastic side that was.

Every connection I’ve ever had with Leeds United, it’s that team. I know

they’ve won the league since but all anybody ever talks about is that Leeds

United side. It’s a long time ago, fifty years ago, and there aren’t many sides

that have carried that reputation for that long. How many people, not just

Leeds fans, can name that team?”

In being given Freedom of the City, Galvin shares an honour

with Nelson Mandela and Winston Churchill. It’s a claim to fame, alongside

being one of the Lads of Leeds and the inventor of the stepover. He starts

laughing again. “It isn’t bad, is it?”