Terry Venables at Leeds — Square Ball 27/11/23

EL TEL

Written by: Moxcowhite • Daniel Chapman

I don’t know if Terry Venables had many encounters with

Leeds fans in the years after he was sacked from managing the club, in 2003. He

wasn’t the sort of manager, or character, many United fans would seek out for

company. I can imagine some awkward glances across Mediterranean hotel bars. A

Leeds fan spotting that trademark perma-tan, those gleaming teeth; Venables

spying a white shirt, a Yorkshire rose tattoo. Maybe mutual nods of

recognition, then each turning away. It would be a shame, because if Venables

ever did sit down with a Leeds fan to compare notes from his time in charge, I

can imagine a lot of common ground. ‘I never knew things were so bad until I

got there,’ Venables might say. ‘We never knew things were so bad until you got

here,’ we might reply.

In some ways Venables was a dream managerial appointment,

but that 2002/03 season woke everybody up. We had, as chairman Peter Ridsdale

famously put it, while Venables was sighing heavily next to him at a televised

press conference, “lived the dream”. Venables could — maybe should — have made

our dreams come true. For Ridsdale and the board, this was the chance to put

their stamp on the football club, rather than David O’Leary’s. When O’Leary got

the job, he was just George Graham’s assistant, with a crowd of kids and a

midas touch — while Ridsdale tried spinning it as a masterstroke, there was no

denying that after Leicester’s Martin O’Neill had turned him down, there had

been no other option but to try O’Leary and get lucky. Now Leeds United — and

Leeds United plc — were leaving luck behind. Terry Venables was no punt.

Venables was the well regarded former Tottenham and Barcelona manager, coach of

the most exciting England national team in modern times. While O’Leary had

spent his summer punditry gig at the World Cup talking himself out of favour

and work, Venables had cultivated charm as a second career since the 1960s,

singing, running nightclubs and boutiques, talking on the television. At times

he had needed that charm, as he was hauled into the High Court for financial

mismanagement, including his move from team manager to chief executive at

Tottenham. He might not have fit many Leeds fans’ idea of a Leeds United

manager — not just a cockney, but the widest of their kind — but he fit Peter

Ridsdale’s idea of what he thought Leeds United should become: a player.

The problem, well, one of the problems, was that Ridsdale

was playing Venables, and did it too well. Venables was not Ridsdale’s choice

for the job — he’d tried again to get Martin O’Neill. But O’Neill was committed

to the last year of his contract with Celtic, and Venables’ charm did its work

on Ridsdale, to a point. He was given a two-year contract, but with a break

option after one, Ridsdale apparently keeping the door open for his first

choice. Until then Leeds needed a manager for right now, and Venables was the

best option, but because Leeds needed him more than he needed the work — he

missed part of pre-season filming a holiday programme with Judith Chalmers —

Ridsdale did his own big sales job on football’s big salesman. It got Venables

through the door. But you can’t kid a kidder for long.

The plan for summer, as Venables understood it, was that

defender and captain Rio Ferdinand would be staying, despite all the public and

private indications that he was moving to Old Trafford. Other players would be

sold instead, raising enough money to fill the club’s shortfalls during another

year without Champions League football, and leaving cash spare for Venables to

spend. The way Venables told it, the illusion lasted as long as an embarrassing

meeting with Ferdinand, to explain how the Leeds team would be built around

him, ending with Rio breaking the news that while that all sounded very nice,

he was off.

Ferdinand went, and one by one Ridsdale’s for-sale list

stayed. Summer moves for Lee Bowyer, Olivier Dacourt, Gary Kelly and Robbie

Keane all fell through — Keane eventually left in September — while Ridsdale

created needless acrimony by telling a supporters’ meeting that David Batty was

effectively retired through injury, which was news to Batty, who threatened

legal action. Players who wanted to stay had been offered around then kept.

Players who wanted to leave had been told to stay. Players who stayed were

annoyed with players who left. Players were eyeing each other’s wage packets,

their status, thinking about transfers and trophies. Players who had been upset

by the club’s handling of Lee Bowyer and Jonathan Woodgate’s court case were

still angry with the board. Everywhere Venables looked there were pissed off

players letting off steam that had been building up for months, if not years.

It’s Venables’ fault that rather than fix things, he made

them worse. His first attempt at enforcing discipline was benching Nigel

Martyn, who didn’t want to travel to Australia for a pre-season tour when he’d

just got back from the World Cup in Japan and South Korea. That denied the team

arguably the club’s greatest ever goalkeeper. He escalated arguments with

Dacourt, offering to ‘drive him to Italy myself’. One move Venables got right

was dropping Bowyer, after a stamp on a Malaga player in the UEFA Cup that the

referee missed, Bowyer’s last act of petulance in a now impossible relationship

with Leeds. But that meant Venables was at odds with an entire first choice

midfield — Bowyer, Batty and Dacourt — and in the next game his own midfield

signing, Paul Okon, made his second start in Bowyer’s place. It soon looked

like two too many.

Amid the acrimony were some good early results, and tactical

ideas and training sessions that several players later said were a level above

anything they’d experienced before. The level of talent waiting in the Academy

was something else that didn’t match ‘the brochure’ Venables said Ridsdale had

sold him, but sifting through the age groups he came up with sixteen-year-old

James Milner, a bright goalscorer in wins over Sunderland and Chelsea as Leeds

won four and drew one over Christmas, quieting the shouts at Elland Road for

Venables to go. His coaching could still be sharp. But the club was becoming

unmanageable.

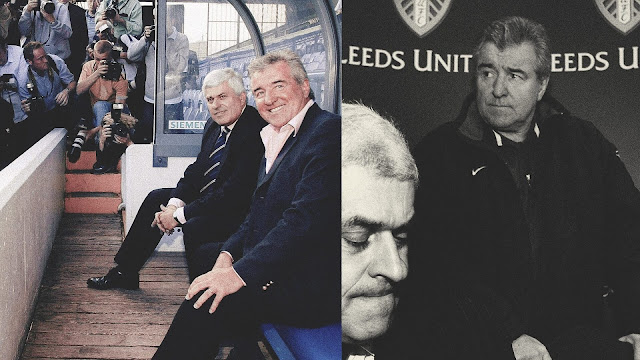

The story of United’s collapse is not really about Terry

Venables. The January transfer window repeated summer, as moves collapsed,

promises were broken, and players Ridsdale told Venables he could keep were

sold. At the end of January, after Ridsdale accepted Newcastle’s bid for

Jonathan Woodgate, Venables was an angry contributor to the infamous press

conference, broadcast live on Sky, when Ridsdale made his ‘lived the dream’

speech. To fans watching at the time, they looked like a single enemy across

the table, joint representatives of the nightmare Leeds was becoming. Watching

it again, though, and knowing what we know now, Venables looks more like a

mirror of the fans’ own feelings, suffering with us through Ridsdale’s attempts

at people-pleasing self-justifications. “As a supporter I did not want to take

the offer,” for Woodgate, he said, but, “I have a primary responsibility to the

shareholders”. Venables was rolling his eyes, and furrowing his brow, and

biting his tongue, and gritting his teeth, and looking as angry and gloomy as

any Leeds fan looked, watching on their televisions, watching him.