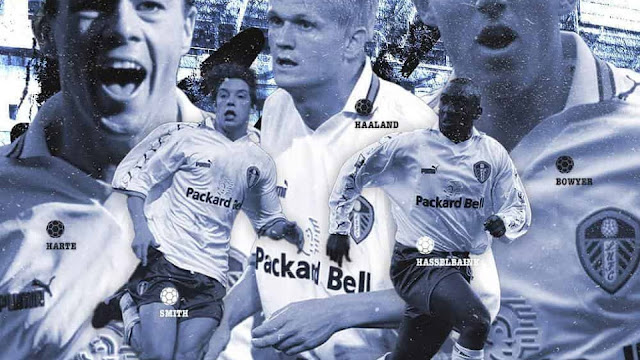

Golden: West Ham vs Leeds, 1st May 1999 - Square Ball 8/3/21

THREE OFF

Written by: Moxcowhite • Daniel Chapman

The first half action at Upton Park was all happening off

camera.

First, nobody could be sure who from Leeds’ team clattered

Eyal Berkovic straight from kick-off, although while he was lying down injured,

everybody saw Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink taking the ball off Ian Wright and

shooting low past Shaka Hislop to put Leeds ahead after 23 seconds. When

Berkovic returned from treatment he had a quiet word with John Moncur, whose

late tackle through Lee Bowyer earned him a booking and cleared up the identity

of the mystery assailant.

Ian Wright got an early yellow card too, for elbowing Alfie

Haaland, then another one after a fifty-fifty challenge with Ian Harte. The

camera caught them coming together after the ball had gone; the next shot

showed Harte lying on the floor in a daze, holding his head, then Wright being

ordered off, and losing his head.

The camera missed what happened between Harte and Wright,

and so did Hammers boss Harry Redknapp, although he had an opinion anyway. “I

didn’t see the incident but I’m disappointed,” he said. Leeds manager David

O’Leary took a different tack. “I know exactly what he did,” he said, “but I

can’t tell you.”

As for Wright’s meltdown, TV showed Trevor Sinclair’s

attempts to restrain him, as he kept lunging at the referee Rob Harris; but

there was only a glimpse of Nigel Martyn, Wright’s old teammate from Crystal

Palace, running fifty yards into the corner of the screen to get his old mate

out of trouble. Lost out of shot was a West Ham supporter leaping from the

Chicken Run stand and trying to kick the linesman, and debris being thrown at

Harte while he lay on the ground.

Wright eventually went down the tunnel with tears in his

eyes, and we have to rely on reconstruction to know what happened next: the

locked door to the referee’s room being kicked off its hinges, Harris’ clothes

being strewn about, a television smashed on the floor. “I don’t even remember

properly what I did, only that I was in the ref’s room,” Wright said. “I hope

and pray to God that I can be forgiven for this stupid and reckless act by the

match officials, the club, the fans and the authorities.”

The teams had only been playing for sixteen minutes. A goal

down and a player down, West Ham were already depleted before the game by

injuries, Rio Ferdinand and Ian Pearce’s absence forcing Steve Lomas and Marc

Vivien Foe into uncomfortable defensive positions. Despite it all, they were

the better side, but saw how their luck was going before half-time — although,

after the delays getting Wright off the field, it was still the sixth minute of

stoppage time. The ref waved play on after David Batty fouled Lomas — “even

Batty seemed ashamed” said one report — and that let Harry Kewell run past Foe,

along the byline and almost to the front post, the ideal spot to put the second

goal on a plate for Alan Smith.

Paulo Di Canio was booked for arguing about that goal

because of course he was, and came out fired up for the second half because of

course he did. After giving the ball to Berkovic wide on the left, he sprinted

into the box for the return pass and scored past Martyn from twelve yards.

Leeds looked unprepared for the situation: the perceived injustice of the first

half had made Upton Park so angry there were six arrests in the crowd and the

referee needed a police escort at half-time. The West Ham players were

channeling that frustration into an attempt that looked highly likely to win

the match.

They were even angrier by full-time, but the game was long

gone by then. Hislop brought Hasselbaink down in the penalty area when the

striker was away from Foe and through. The penalty was obvious, the red card

all but unavoidable according to the law; Scott Minto, in the foreground, had

his head in his hands before Hislop was back on his feet. Craig Forrest came on

for Berkovic and went in goal, but Harte scored easily to make it 3-1. The West

Ham fans, whose opinion of Harte was low enough after the first half, did not

enjoy his somersault, or that he was spinning in front of a stand full of

ecstatic Leeds fans, a cheerful pile of white and yellow replica shirts in the

early summer sunshine.

With ten players and one goal needed to equalise, West Ham

had felt they had a chance; down to nine and two behind they just felt pissed

off. By the end, only Berkovic, Sinclair and Frank Lampard Junior, of West

Ham’s starting eleven, avoided being shown a card. Leeds, meanwhile, avoided

their upset players. Hasselbaink backheeled Haaland’s pass into space on the

edge of the penalty area, and either time stood still or it was the Hammers

defence, waiting and watching for Bowyer to run onto the ball and hit a shot,

first time, into Forrest’s bottom corner. A minute later, with the game

compressing on the left, Hasselbaink passed to Haaland, standing alone in half

a pitch on the right. He took the ball into the box and kicked it across

Forrest into his other bottom corner, then set off to high-five the front row

of fans behind the goal.

At 5-1 there was only one thing left for West Ham to do: go

down to eight players, Lomas getting sent off in the 87th minute for a

two-footed lunge at Harte. Leeds did get a few yellows of their own: Batty for

a foul on Lampard, Smith inevitably, Clyde Wijnhard. But the Hammers were in a

league of their own for indiscipline, while thanks to this win Leeds qualified

for the UEFA Cup, with three games left to try getting into the Champions

League.

“Frankly, I thought we were disappointing,” said O’Leary,

who had been in an argumentative mood all week. His predecessor Howard

Wilkinson, whose blueprints from 1988 built the Thorp Arch Academy now

supplying five of United’s starting eleven, had given an interview about their

progress. “There are so many people that deserve credit for the way the kids

have emerged into such good players,” he said. O’Leary wasn’t impressed. “They

were only thirteen-year-olds when he had them. A lot happens from then on. This

is my team now. I have worked with them for the last two years with Eddie

Gray.”

Due next was a summer of transfers and contracts. O’Leary

had a new five year deal; so did Alan Smith. But some players had to go —

Wijnhard, Lee Sharpe, Danny Granville, Derek Lilley — and others wanted more

money to stay. A survey had just been published into spiralling wages, claiming

Newcastle’s Duncan Ferguson was the highest paid player in the Premier League

at £40,000 per week, even ahead of his teammate Alan Shearer’s £35,000. Leeds

chairman Peter Ridsdale was sounding a note of caution and financial sense.

Clubs needed, he said, “to face up to the reality that transfer fees and wages

must not be allowed to continue to grow at levels that are unsustainable.”

Try telling that to Jimmy Hasselbaink. His goal — not to

mention two assists and a penalty won — pushed him ahead of Andy Cole and

Dwight Yorke to one goal behind injured Michael Owen in the race to be Premier

League top scorer.

“Of course I would love to win the golden boot,” he said.

“I’m a striker and it’s my job to score goals. Maybe if I finish with the most

goals in England then the club will give me the contract I have heard so much

about.”